In September 1987, countries from around the world came together to sign the Montreal Protocol. The goal of the protocol was to reduce the damage being done to the Earth’s ozone layer, which at the time was seen as one of the most pressing dangers facing humanity.

Over 98% of ozone-damaging substances have been phased out since the introduction of the protocol, and it is estimated that up to 2 million cases of skin cancer have been prevented.

It is a testament to the power of science and global action that the ozone layer has been largely repaired.

The problem with the ozone layer may have been solved, but we are still faced with daunting, complex environmental challenges. One of these challenges is the issue of plastic pollution. The world’s oceans contain an estimated 15-51 trillion pieces of plastic, including microplastic particles that are being ingested by marine animals.

The world came together and tackled the ozone layer problem. Can we do the same with plastic pollution?

In this article, we look at some of the scientific and technological solutions either proposed or underway that seek to reverse the devastating effects of plastic pollution.

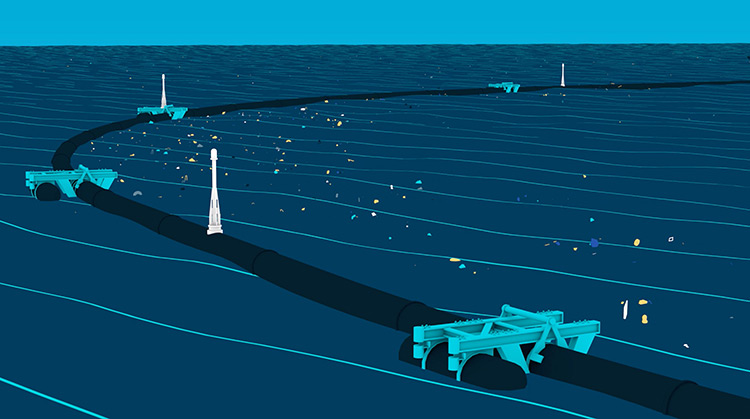

1. The Ocean Cleanup

In 2011, 16-year-old Boyan Slat was scuba diving on vacation in Greece. While exploring the seabed, the teenager from The Netherlands was struck by the amount of plastic floating nearby.

Boyan, being an industrious and proactive teenager, dedicated himself to investigating solutions to the problem of plastic pollution in the ocean.

His work led him to his presenting a TedX talk in 2012, where he described his idea to build a passive system that could be used to clean up plastic in the ocean.

Showing incredible drive and tenacity, Slat continued to pursue his goal of cleaning up the ocean, and in 2013 founded the non-profit organisation, which he called ‘The Ocean Cleanup’.

Through crowdfunding and donations from Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, The Ocean Cleanup raised over $31.5 million USD to turn their ideas into reality.

The system

The Ocean Cleanup system consists of 600-meter long floating structures, which act as a containment boom, concentrating marine debris. The system will utilize the wind, waves and ocean currents, making it a ‘passive’ system, meaning it does not have any form of propulsion. Once the debris has been collected inside the containment area, it can then be collected.

The floating structures will collect debris floating on the surface of the water, while a 3-meter deep skirt collects debris underneath the water level.

Once the system has collected a sufficient amount of debris, it will be collected by a nearby vessel, known as a ‘garbage truck of the seas’.

The plastic collected will be taken back to land, where it will be sorted, and recycled where appropriate.

Where will it operate?

In October 2018, the Ocean Cleanup system arrived at its destination: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, located about halfway between Hawaii and California.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a vast area of plastic debris. A recent study estimated to cover an area four times the size of France.

It has been estimated that 45% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is made up of abandoned fishing fear, otherwise known as ‘ghost gear’.

As well as large pieces of plastic like fishing nets, the area also contains a huge amount of microplastics – pieces of plastic smaller than 5 mm in diameter. The Ocean Cleanup system has been designed to account for these tiny plastic particles.

The Ocean Cleanup says there are more than 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic in the patch, weighing an estimated 80,000 tonnes.

The goal of the Ocean Cleanup

This ambitious project has an ambitious aim: to clean up 50% of the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch within 5 years.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not the only garbage patch in the world – four other smaller patches exist elsewhere in the world. In time, the Ocean Cleanup team hope to deploy their system into every garbage patch in the world.

They ultimate goal is to be able to remove 90% of plastic in the ocean by 2040. An ambitious goal, but one that is already well underway.

Follow the progress of the Ocean Clean by visiting their official website: https://theoceancleanup.com/

2. The plastic-eating enzyme

Plastic decays differently to organic materials such as food or paper. Rather than being digested by bacteria, plastic breaks down when exposed to sunlight, in a process called photodegradation.

The incredible durability of plastic is the main reason why ocean plastic pollution is such a huge concern. If plastic were to disappear after a couple of weeks, it would not be a big problem. As it stands though, plastic takes decades, or even centuries, to decay. And as it decays, it breaks into smaller and smaller pieces, which are easily ingested by marine life.

The discovery

Up until recently, it was thought that bacteria can not break down plastic in the same way that it breaks down organic material. The molecular bonds of plastic were thought to be too strong to attract bacteria.

However, in 2016, scientists in Japan discovered an enzyme capable of breaking down one of the world’s most used plastics – PET (polyethylene terephthalate), which is used to make plastic bottles and food containers. To give you an idea of the ubiquity of PET, around 1 million plastic bottles are sold every minute around the world.

The newly discovered enzyme has been named Ideonella Sakaiensis 201-F6. Scientists believe it evolved to eat plastic due to the accumulation of large amounts of plastic over the last 70 years.

Enzo Palombo, a professor of microbiology at Swinburne University explained: “If you put a bacteria in a situation where they’ve only got one food source to consume, over time they will adapt to do that. I think we are seeing how nature can surprise us and in the end the resiliency of nature itself.”

Improving the efficiency of the enzyme

An international team of scientists have managed to improve the efficiency of the enzyme at breaking down plastics. Tweaking the molecular composition of the enzyme made it able to consume PET 20% faster than before.

Prof John McGeehan of the University of Portsmouth, who led the research, said: “It gives us scope to use all the technology used in other enzyme development for years and years and make a super-fast enzyme.”

Hope for the future

The discovery of a plastic-eating enzyme is very exciting, as it was previously thought that bacteria completely avoided any form of plastic, and would inevitably last for hundreds of years.

The potential practical applications for this new enzyme are still being investigated. One idea put forward is to spray the enzyme on floating garbage patches in the ocean. This isn’t currently feasible, however, because PET sinks in seawater.

Scientists are hopeful that other forms of bacteria will be found that are able to consume different types of plastic.

Research into this new plastic-eating enzyme is still at an early stage, but it is clearly one of the most exciting environmental discoveries in recent years. In time the enzyme could become a real asset in the fight against the widespread plastic pollution blighting our planet.

3. Converting plastic to fuel

Around 300 million tonnes of plastic are produced worldwide each year, and only about half of this plastic can be recycled. This has resulted in our planet being swamped with plastic – both in landfills and in our oceans.

More and more people are becoming conscientious about their plastic use – reducing the amount they use whenever they can. But the fact remains, there are millions of pieces of plastic already out there, and it can take centuries to decay.

So what can be done to tackle the astronomical amount of plastic already in existence?

An Australian company, Licella, think they have the answer. Their plan is to convert end-of-life plastics (plastic that can not be recycled) into oil. Their ‘Catalytic Hydrothermal Reactor’ can melt plastics into liquid fuel.

Dr Len Humphreys, chair of Licella explains: “This investment will allow for the deployment of our technological solution on a commercial scale, with up to 20,000 tonnes to be transformed from waste to product annually from next year just from the first plant alone“.

Learn more about the process on Licella’s website: http://www.licella.com.au

The process, however, is not without its critics. It has been called an environmental trade off.

Dr Tom Beer, honorary fellow at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) said: “It depends what you value most, do you want to get plastic out of landfill, and out of the oceans, then fantastic, but it does mean carbon emissions.”